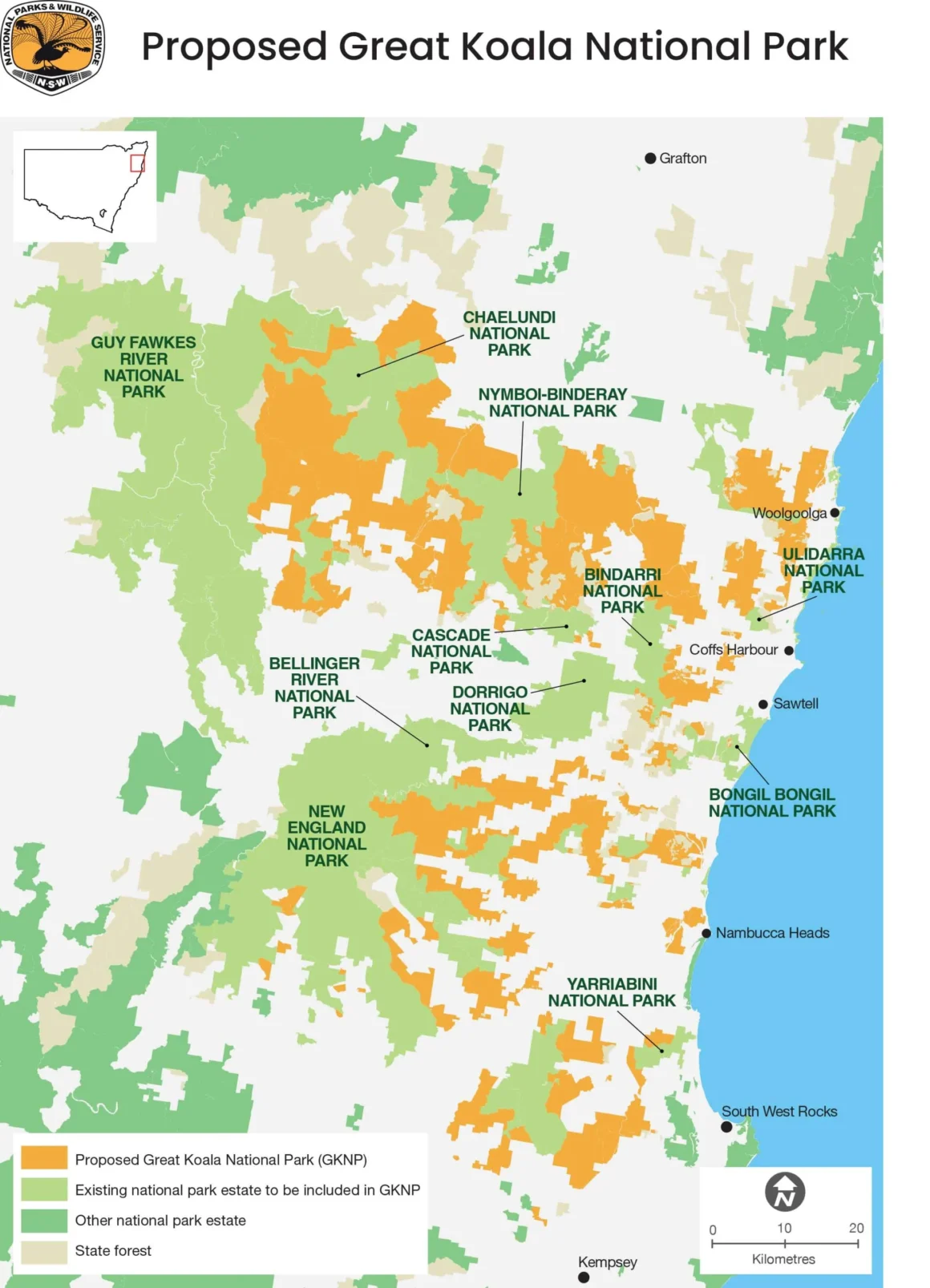

The Great Koala National Park would be one of the largest protected areas ever created in NSW. Spanning more than 475,000 hectares, it’ll stretch from Kempsey to Grafton and inland toward Ebor, covering a huge slice of the Mid North Coast and adjacent ranges.

The plan would combine existing national parks and reserves with around 176,000 hectares of newly protected land. The stated aim is to create a connected habitat corridor for threatened wildlife, including more than 12,000 koalas and tens of thousands of greater gliders.

On paper, it’s hard to argue with the conservation intent. The area is home to more than 100 threatened species, plus rare orchids, cockatoos and other native wildlife. The NSW Government has committed $80 million to develop the park, with another $60 million allocated to National Parks and Wildlife Service to support its establishment.

This isn’t a small or symbolic change. It’s a fundamental shift in how a massive chunk of forested land is classified, managed and accessed. Once that shift happens, it’s very difficult to reverse.

That’s why this stage matters. The government is still deciding how the park will work in practice, not just where the boundaries sit on a map.

Why 4X4 Access Is Part Of The Conversation

Unlike many past park announcements, the NSW Government is openly asking 4X4 clubs how the area is currently used. That’s a critical detail, and one worth paying attention to.

Much of the proposed park footprint includes existing state forests and reserves. These aren’t untouched wilderness zones. They’re working landscapes with fire trails, access roads, historic routes and informal touring tracks that have been used responsibly for decades.

4X4ers already play a role in how these areas function. Clubs maintain tracks, report damage, assist with clean-ups and help discourage illegal behaviour through regular use. In many cases, vehicle access supports land management rather than undermining it.

The government has indicated the park will be made up of multiple reserves, each with different rules. That opens the door to nuance, rather than blanket bans. Seasonal access, designated touring routes and managed closures are all options if they’re baked in early.

History shows what happens when they aren’t. Temporary closures quietly become permanent. Fire trails get reclassified. Access disappears without much explanation.

This consultation is where those outcomes can still be influenced. Once legislation is passed, the conversation usually shifts from “how should this work” to “why can’t we drive here anymore”.

Consultation Only Works If People Show Up

An online survey is now live through the NSW Have Your Say website, and it’s open to anyone who uses the area now or plans to in the future. That includes recreational drivers, touring groups and organised 4X4 clubs.

This isn’t about shouting opposition to the park itself. That approach rarely gets traction and usually gets ignored. The smarter move is to clearly document how the land is used, which tracks matter, and why access should be retained.

Decision-makers don’t respond well to vague frustration. They do respond to specific, reasonable input that shows how vehicle access can coexist with conservation goals.

That means explaining which routes are key touring links, which areas are popular for camping, and how closures would affect regional travel and local economies. It also means acknowledging environmental values and pushing for sensible management, not unrestricted access.

Silence is often interpreted as agreement. If 4X4ers don’t contribute now, future restrictions will be framed as unavoidable rather than contested.

Consultation doesn’t guarantee a perfect outcome, but absence almost guarantees a bad one. This is the part of the process where the record is set, and that record matters later.

Why This Sets A Precedent Beyond NSW

The Great Koala National Park won’t be the last proposal of its kind. Large-scale conservation projects are becoming more common, especially in areas that overlap with popular touring regions.

How this one is handled will influence future decisions, both in NSW and elsewhere. If balanced access is protected here, it becomes a reference point. If it’s slowly eroded, it becomes a warning.

4X4ing doesn’t need to be framed as incompatible with conservation. In many cases, it already operates alongside it. The challenge is ensuring that reality is recognised in policy, not erased by default.

This is also about credibility. If governments want community buy-in, they need to show that consultation leads to real outcomes. If access is removed regardless of feedback, people stop engaging altogether.

For 4X4ers, this is a moment to move beyond reactive outrage and into proactive involvement. Clear, calm input now has far more impact than complaints later.

If you value touring the Mid North Coast, exploring state forests responsibly, or keeping access decisions grounded in how land is actually used, this is one survey worth filling out.

Because once the gates close, they rarely reopen.